Shawn Evans

Philosophies and Practices of Preservation among Pueblo People

In 2011, Shawn Evans received a Fitch Mid-Career grant to study the range of preservation philosophies of the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas. These centuries-old villages represent the oldest continual architectural tradition in the United States but are threatened by underutilization, deterioration, and the loss of traditional building practices. The study will review the physical conditions of the Pueblo villages, examine the past and present traditions for preservation of the historic housing, and provide an opportunity for the Pueblos to discuss their varying self-determined approaches. Results of the study will be presented and published in a manner deemed appropriate by the tribes. The study builds on the research and planning by Mr. Evans, Atkin Olshin Schade Architects, and the Ohkay Owingeh Housing Authority for the ongoing rehabilitation of the historic core of Ohkay Owingeh.

** UPDATES **

NOV 2016 Owe’neh Bupingeh Preservation project at Ohkay Owingeh featured in the exhibit “By the People: Designing a Better America,” at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (NYC). [more]

SEPT 2016 Shawn Evans presented at APT National conference in San Antonio, TX. [more]

NOV 2014 “Ohkay Owingeh, the Owe’neh Bupngeh Preservation Project” won a national preservation award from the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.

NOV 2014 Shawn Evans spoke at the first New Mexico Building Creative Communities Conference, focusing on the implications of his Ohkay Owingeh project.

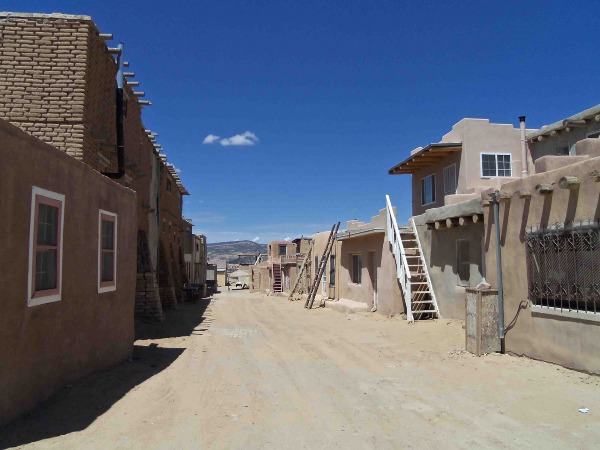

Acoma Pueblo. Photo by Shawn Evans.

The image above was taken by Mr. Evan’s during a research trip in Fall 2011. Below is his field report:

Preservation is always about more than bricks and buildings. This truth is perhaps strongest when dealing with tribal preservation, where preservation is, in fact, rarely about buildings. Several major studies of tribal preservation have been completed, notably the Keepers of the Treasures report by the National Park Service (1990) and Andrew Gulliford’s book, Sacred Objects and Sacred Places (funded by a 1991 Fitch grant and published in 2000). These and other studies effectively demonstrate that historic preservation must be understood as a component of a broader cultural preservation effort. Contemporary Native Americans are engaged in an urgent effort to sustain their cultural traditions, particularly their endangered languages, yet many view preservation standards as another means of the government to meddle in Indian affairs. For whom are indigenous objects, structures, and landscapes to be preserved? Whose value systems determine treatment methods or if built heritage is to be preserved at all?

This study aims to examine the preservation philosophies of the 21 pueblo tribes in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. These historic villages, some as old as 1,000 years, maintain the oldest architectural traditions in the United States. Although the villages are quite varied in their physical organization, the historic homes are constructed in just a few variations of spatial typologies and tectonic systems. Many of the villages are in poor condition, having suffered abandonment due to changing lifestyles and HUD policies. Compounding the abandonment is the fact that the Portland cement, installed within the last two generations as a replacement for the traditional mud plasters, has caused extensive damage through the retention of moisture in the adobe walls. Native American tribes only gained sovereignty over the decision making process for federal housing expenditures in 1996, thus the planning and implementation of broad self-determined preservation plans is a recent effort.

The study began with background research and the gathering of historic photographs. The photo collection (still in process) numbers over 2,000 images, organized by tribe, photographer, and chronology. The images demonstrate the organic nature of each village, which all existed long before the advent of film. The earliest images provide an understanding of the homes prior to major influences of western civilization. The homes were accessed via ladders and hatches and light was admitted through simple apertures in the walls or through thinly cut translucent stone. The architectural change of the pueblos is documented in the photographs, which catalog when various adaptations were made at each pueblo, primarily following advances in transportation from trails to rails to highways.

Preservation and housing leaders at the pueblos have been eager to meet with me to discuss their perspectives and learn about the efforts of other tribes. As I anticipated, the philosophies and practices are quite varied. Of the tribes I have met with thus far, Ohkay Owingeh and Taos Pueblos have developed the most particular practices. I am very familiar with Ohkay Owingeh, having assisted in the development and implementation of their preservation plan. At this pueblo, the community determined that the most appropriate preservation treatment was full rehabilitation. The exteriors of the homes are being returned to their multi-storied massing, with historically appropriate mud plaster and wood doors and windows as seen in early 20th century views, while the interiors are being adapted with contemporary conveniences. Use of federal housing grants has required a difficult balancing of preservation and housing standards. Taos Pueblo, on the other hand, long ago determined that their historic village should be maintained as it has been for generations – architectural change is restricted and no utilities are permitted within the walls. Consequently, very few of the several hundred homes in the iconic structures are fully inhabited. They are currently completing a pilot preservation project and developing a preservation plan funded by the World Monuments Fund. Each group of elders from the various tribes has expressed different priorities for preservation. Some favor the preservation of exterior appearances with less concern for the interior, while others are more focused on dirt floors and fireplaces as direct and private connections to the earth and those who came before.

Historic preservation of the physical fabric of the homes is a new concept for the tribes. Traditionally the homes were understood to be of the living earth. They were nourished and cared for, but when the homes grew too small or were too deteriorated, they were demolished and rebuilt to suit changing needs. A number of the officials I have met with continue to hold this practical view. While most would prefer the homes to be built in the traditional ways, many openly accept and advocate for modern materials. In every case, however, there is an understanding that the gatherings of homes are the containers of the earthen plazas, the ceremonial hearts of these cultures. The preservation of these open spaces is essential to the survival of these peoples.

“View of [Ohkay Owingeh] Pueblo and North Plaza,” 1877. John K. Hillers, photographer. Courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution (NAA INV 06344100)

Read about Shawn’s work in the Pennsylvania Gazette